North Korea said Wednesday its leader, Kim Jong Un, suspended planned military retaliation against South Korea in an apparent slowing of a pressure campaign it has waged against its rival amid stalled nuclear negotiations with the Trump administration.

Last week, North Korea declared that relations with South Korea had fully ruptured. It destroyed an inter-Korean liaison office in its territory and threatened unspecified military action to censure Seoul for a lack of progress in bilateral cooperation and for anti-North Korean leaflets that activists have floated by balloon across the border.

Analysts say North Korea, after deliberately raising tensions for weeks, may be pulling away just enough to make room for South Korean concessions.

In a separate statement, a senior North Korean ruling party official said the future of inter-Korean relations would depend on the South’s “attitude and actions.”

Get New England news, weather forecasts and entertainment stories to your inbox. Sign up for NECN newsletters.

If Kim Jong Un does eventually opt for military action, he may resume artillery drills and other exercises in front-line areas or have ships deliberately cross the disputed western maritime border between the Koreas, which has been the scene of bloody skirmishes in past years. However, any action is likely to be measured to prevent full-scale retaliation from the South Korean and U.S. militaries.

The North's official Korean Central News Agency said Kim presided by video conference over a meeting Tuesday of the ruling Workers’ Party’s Central Military Commission, which decided to postpone plans for military action against the South proposed by the North’s military leaders.

KCNA didn’t specify why the decision was made. It said other discussions included bolstering the country’s “war deterrent.”

U.S. & World

The agency later published a statement by Kim Yong Chol, vice chairman of the Workers’ Party’s Central Committee, who ridiculed South Korean Defense Minister Jeong Kyeong-doo for his comments during a parliamentary session expressing confidence in the South’s military preparedness and urging the North to completely withdraw its threat of military action.

“While this may sound like a threat, it won’t be fun (for the South) when our ‘postponement’ becomes ‘reconsideration,’’’ Kim Yong Chol said.

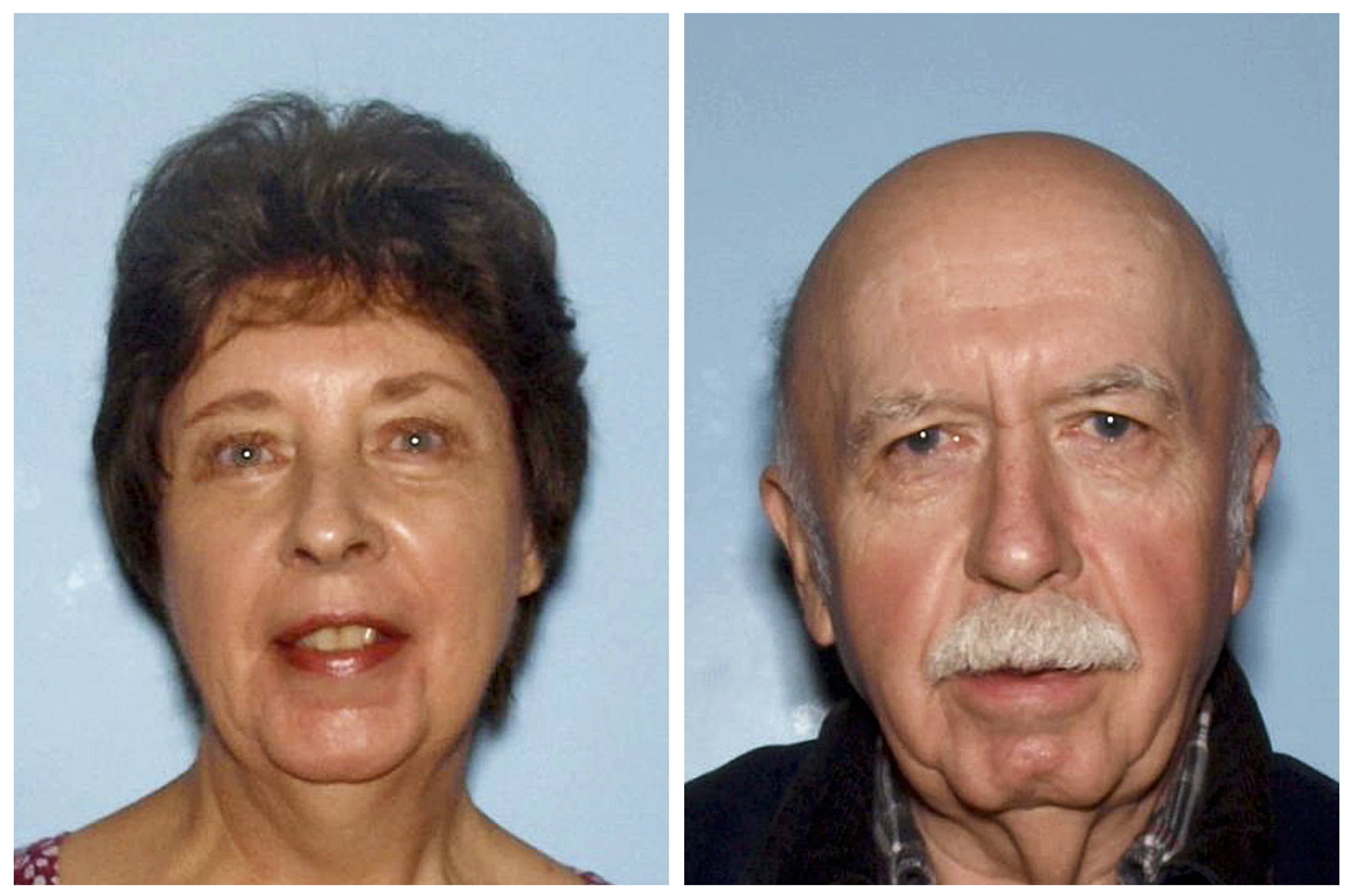

As North Korea’s former top nuclear negotiator, Kim Yong Chol traveled to Washington and met President Donald Trump twice in 2018 while setting up summits with Kim Jong Un.

Yoh Sang-key, spokesman of South Korea’s Unification Ministry, said Seoul is “closely reviewing” the North’s reports but didn’t further elaborate.

Yoh also said it was the first report in state media of Kim holding a video conferencing meeting, but he didn’t provide a specific answer when asked whether that had something to do with the coronavirus.

North Korea says it hasn't had any COVID-19 cases, but its claim is questioned by outside experts.

Kim Dong-yub, an analyst from Seoul’s Institute for Far Eastern Studies, said it’s likely that the North is waiting for further action from the South to salvage ties from what it sees as a position of strength, rather than softening its stance toward its rival.

“What’s clear is that the North said (the military action) was postponed, not canceled,” said Kim, a former South Korean military official who participated in inter-Korean military negotiations.

Other experts say the North is seeking something major from the South, possibly a commitment to resume operations at a shuttered joint factory park in Kaesong, which was where the liaison office was located, or restart South Korean tours to the North’s Diamond Mountain resort. Those steps are prohibited by the international sanctions against the North over its nuclear weapons program.

The North has a history of dialing up pressure against the South when it fails to get what it wants from the United States. The North’s recent steps came after months of frustration over Seoul’s unwillingness to defy U.S.-led sanctions and restart the inter-Korean economic projects that would breathe life into the North's broken economy.

“Now isn’t the time for anyone in Seoul or Washington to be self-congratulatory about deterring North Korea,” said Leif-Eric Easley, a professor at Ewha University in Seoul.

“There may be a pause in provocations or Pyongyang might temporarily deescalate in search of external concessions. But North Korea will almost certainly continue to bolster its so-called ‘deterrent.’ As long as the Kim regime refuses to denuclearize, it is likely to use Seoul as a scapegoat for its military modernization and domestic politics of economic struggle after failing to win sanctions relief.”

The public face of the North’s recent bashing of the South has been Kim Yo Jong, the powerful sister of Kim Jong Un who has been confirmed as his top official on inter-Korean affairs. Issuing harsh statements through state media, she said the North’s demolishing of the liaison office would be just the first in a series of retaliatory actions against the “enemy” South and that she would leave it to the North’s military to come up with the next steps.

The General Staff of the North’s military has said it would send troops to the mothballed inter-Korean cooperation sites in Kaesong and Diamond Mountain and restart military drills in front-line areas. Such steps would nullify a set of deals the Koreas reached during a flurry of diplomacy in 2018 that prohibited them from taking hostile actions against each other.

In condemning the South over anti-North leaflets floated by North Korean refugees across the border, North Korea said Monday that it printed 12 million of its own propaganda leaflets to be dropped over the South in what would be its largest ever anti-Seoul leafleting campaign.

It wasn’t immediately clear whether Kim Jong Un’s decision to hold back military action would affect the country’s plans for leafleting. The North’s military had said it would open border areas on land and sea and provide protection for civilians involved in the leafleting campaigns.

Nuclear negotiations between North Korea and the U.S. largely stalled after Kim’s second summit with Trump last year in Vietnam, where the Americans rejected North Korea’s demands for major sanctions relief in exchange for a partial surrender of its nuclear capabilities.