For nearly a decade, a murder in New Bedford could have been solved, prosecutors say. Hiding in plain sight was a rape kit that hadn't been tested 14 years prior.

Through a coincidental and meandering turn of events, the woman's murder would help uncover an accumulation of rape kits that prosecutors say has led to criminals remaining free for years on end.

"That was very disturbing," Bristol County District Attorney Tom Quinn said. "But we did something about it."

That case revealed to Quinn and his office that there was a statewide backlog of sexual assault collection kits that hadn't been fully tested, including more than 1,100 in Bristol County, according to prosecutors there.

Through a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice, the Bristol County District Attorney's Office is nearly done testing all of its kits by a private lab in Virginia. It's expected to wrap up soon, and the renewed focus on cracking cold cases already has resulted in new charges being filed in decades-old assaults.

Bristol's backlog is just a fraction of the backlog faced by the state. After years of scrutiny and attempted legislative solutions, Massachusetts has recently begun making faster progress toward ending its own sexual assault evidence kit backlog that dates back over two decades.

The state crime lab, overseen by the Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety and Security, is using the same private lab to process sexual assault kits from other jurisdictions across the Commonwealth. The lab said it has made “significant” progress in testing the 6,502 kits that were determined to need review under recent legislation, but numbers provided to NBC10 Boston showed over 2,500 were still waiting to be tested.

Nearly the same amount were deemed to not need testing for a plethora of reasons.

The idea that the small percentage of survivors who have the courage to actually file a police report with their sexual assault evidence kit was not taken seriously and just sat on a shelf, not fully tested, not fully investigated — it makes me angry.

Rep. Natalie Higgins

While the end is in sight for Bristol County, the state still has a ways to go — it has recently picked up the pace in ending the statewide backlog, despite new legislation and years of public pressure.

Advocates worry about the damage already done: compounded trauma that survivors may have faced learning their kits haven't been fully tested, and perhaps a further erosion of trust in the criminal justice system among survivors of an already underreported crime.

"I think it makes people feel ... unseen, unheard, minimized, disrespected and not prioritized," said Sharon Imperato of the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center. "People are watching."

Resources for victims of sexual assault are available through the National Sexual Violence Resources Center and the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline at 800-656-4673, and Massachusetts provides this list of statewide and resources for sexual assault survivors.

Bristol County's Push

When Bristol County prosecutors discovered the state lab’s backlog of kits for their cases several years ago, they took matters into its own hands.

“We conducted a review through the state lab and then the departments as to how many outstanding kits have not been fully tested,” Quinn said in an interview.

They found over 1,100 in their county, which left Quinn "very upset," he said: "The lab did not fully test these kits, which they should have. So, it was a failure of the state lab."

The state crime lab processes sexual assault kits for law enforcement jurisdictions across the Commonwealth, except for the Boston Police Department, which has its own lab.

Convicted killer John Loflin was the person whose crimes shed light on the statewide backlog for Bristol County prosecutors.

He killed Marlene Rose in New Bedford in 2002, but was only arrested in 2011 — in Tennessee, on unrelated charges. Those investigators collected his DNA, which ended up matching his DNA to Rose's murder, and he was convicted in 2013.

Bristol County's review followed Loflin's conviction, but investigators could have had access to his DNA earlier. That’s because Loflin was also charged in a 1997 New Bedford rape case that was eventually dismissed because the alleged victim left the country. The victim, though, had a rape kit done, which was submitted to the lab.

The kit never got fully tested, “unbeknownst to law enforcement," according to Bristol County prosecutors.

Had the kit been tested, prosecutors said, Loflin would have been arrested in 2002 following the murder, because forensic evidence from the murder victim would have matched his profile entered from the 1997 rape kit. Instead, he was free for nearly a decade more — something Quinn called "disturbing."

"To some extent, since we're going back in time, it can make it a little more difficult," Quinn said, referring to testing old kits. "But this is what should be done from the beginning. Because it's a professional way of dealing with the situation. It's the right thing to do."

Quinn’s office applied for and received the Justice Department grant to go through Bristol County’s share of the sexual assault kit backlog, which consisted of 1,148 kits, according to Quinn. The grant money was deposited into the office’s account in June 2019, and Bristol County prosecutors hired a retired Massachusetts State Police detective to help with inventorying and prioritizing the kits.

The COVID-19 pandemic created delays, but in April 2021, the DA’s office sent its first batch of kits to be tested at Bode Laboratories, the same lab in Virginia being used by the state.

All of Bristol County’s untested kits are now expected to be fully tested by the end of January, despite a “slow start,” according to Quinn’s office.

“We're doing it because it's the right thing to do,” Quinn said. “It’s very time consuming. A lot of effort has gone into this. But I think it’ll get a lot of satisfaction when these kits are fully tested.”

Bristol County’s initiative has already resulted in multiple cases seeing major developments, like charges being brought against suspects identified through the DNA testing. Quinn said that uploading these DNA profiles to the national Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) — a national database of DNA maintained by the FBI — could help crack unsolved cases elsewhere, too.

Using DNA to Catch Rapists

DNA evidence extracted from sexual assault collection kits has proven to be an important tool for law enforcement investigating sexual assault cases. For it to work, a suspect must already be in the federal DNA database — usually from being charged in another crime. Many rapists have had prior run-ins with the law, though, which makes it possible for prosecutors to catch them with DNA.

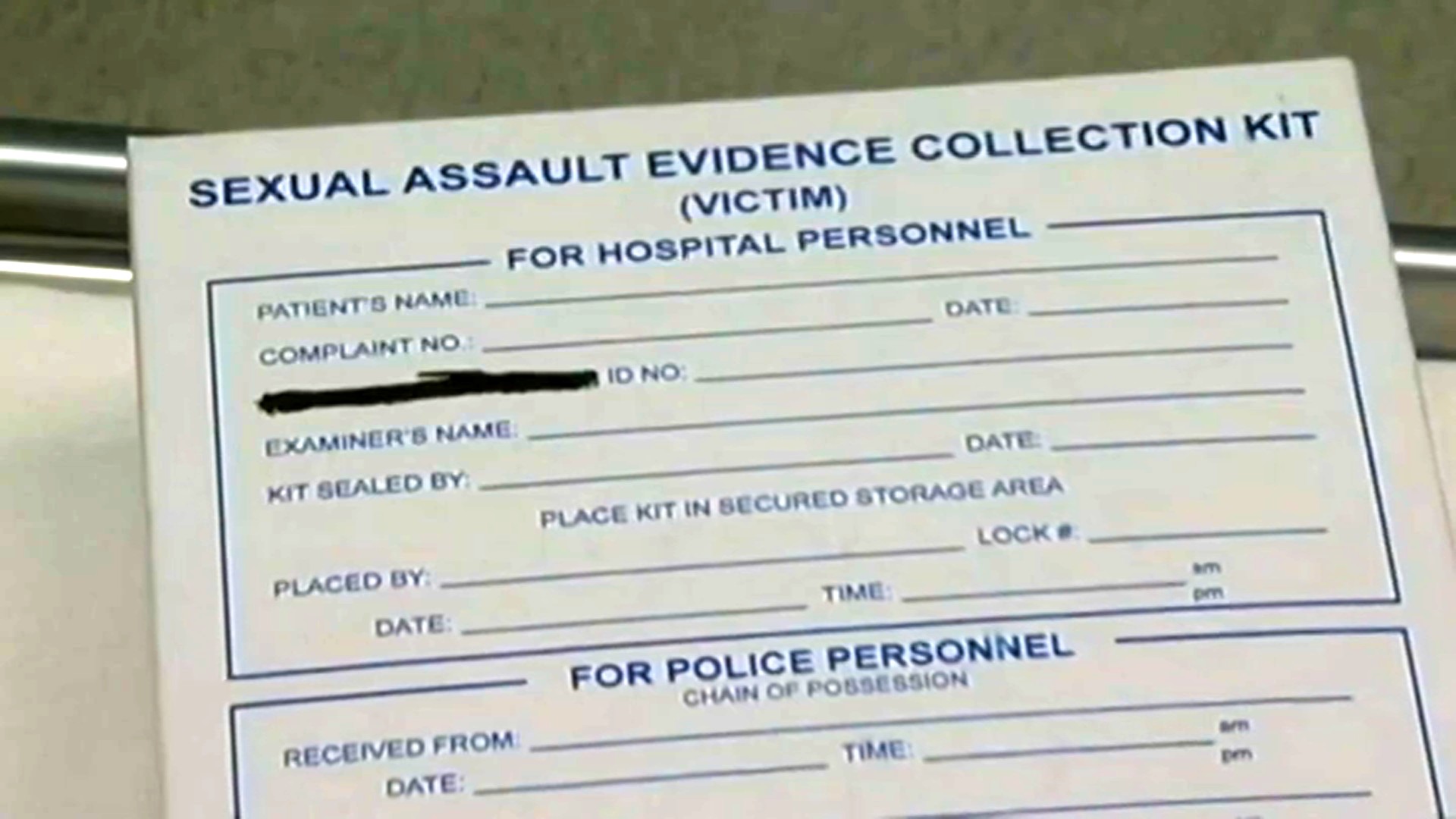

A sexual assault evidence collection kit — often abbreviated to SAECK — is an invasive tool that is administered by a medical professional after someone is raped to acquire genetic material that may be left behind in the sexual assault. The kits are administered by trained medical professionals, typically at hospitals, and can take hours to complete.

After a sample is collected from the person who was assaulted, the kit is handed off to law enforcement, where two stages of tests are performed. The first test determines whether there is a viable sample contained in the kit that is fit for DNA extraction. The second part of the testing procedure processes the kit for DNA sequencing.

If a lab can extract a DNA sequence from the kit, that information is then uploaded to CODIS, the FBI's database. If the DNA from the rape kit matches a sequence that’s in the system, law enforcement can identify a suspect.

Survivors, Quinn said, have been relieved when they hear news that an arrest was made in their case.

“I am very pleased for them, that they can feel vindicated ... by charges being brought in these cases," Quinn said. "And also, just hanging in there with what they've had to endure, probably psychologically, knowing that the person who sexually assaulted them is out there, and who knows if they’re in their community.”

John Loflin was sentenced to life in prison.

State Lab Making 'Significant Progress' as Bristol County Nears Completion

While Bristol County is nearly done clearing its backlog of tests thanks to federal money, the state lab still has a ways to go. Progress appeared slow for months, but has recently picked up significantly, based on the most recent available numbers, which the state provided to NBC10 Boston.

Out of the 6,502 total kits that needed to be reviewed for testing by the state, 628 had been tested as of November. Out of those 628, a total of 91 kits resulted in data being uploaded to the CODIS system, which equates to around 14.5%.

Massachusetts’ Executive Office of Public Safety and Security keeps record of the Massachusetts State Police Crime Lab’s progress toward processing the backlog of sexual assault kits and is required by recent legislation to release quarterly reports to the public with updates. Like Bristol County, the state is partnering with Bode Technology in Fairfax County, Virginia, to get the kits processed.

November’s data represented two major shifts since the previous months, including a much faster cadence in getting kits tests done and a higher percentage of kits that resulted in DNA profiles being uploaded.

Where 61 tests kits were tested as of March, 628 have been as of November. Between October and November, 173 tests were processed, nearly as many as were tested in the months between June and October. And in October, only about 9.5% of the kits tested at that point ended up on CODIS.

As of November, there were 2,664 kits still waiting to be tested, with another 753 waiting for a response from their respective district attorneys. Testing was determined to not be required for 2,457 of the total number of kits.

“The Commonwealth’s process for sexual assault evidence kit collection and testing is regarded as a national standard, and Massachusetts has the fastest turnaround time in the country,” an EOPSS representative wrote in a statement to NBC10 Boston. “The Crime Lab has made significant progress in testing previously untested kits, but for the kits that remain, the Lab must wait for approval from a District Attorney before proceeding.”

“This is an ongoing process, and the Administration is committed to delivering justice for survivors of sexual assault,” the statement continued. “The Administration has also advanced numerous key initiatives to better support survivors, strengthen law enforcement’s response to sexual assault, and improve outcomes.”

One of those initiatives was the development and launch of Track-Kit, which is an online tool survivors can use to track the status of their kit, connect to people involved in their case and get access to resources. The Sexual Assault Evidence Collection Kit Team was recognized in December by the state with the Manuel Carballo Governor’s Award for Excellence in Public Service, an award for state workers who “exemplify the highest standards of public service.”

New Charges in Old Cases

There have been several people who have recently been charged in cold cases that went unsolved for years.

Eduardo Mendez was arrested last month in a rape that happened in June 1994 in Attleboro, Massachusetts. Investigators were able to match the DNA in a kit that was previously not fully tested to Mendez, who was in the national DNA system from a stabbing conviction in New York later in the 1990s, according to Bristol County officials. The case was sent to a private lab through a federal grant received by the state, prosecutors and state officials said.

Earlier this year, authorities arrested Dylan Ponte in connection with the cold case rape of a 16-year-old in New Bedford in 2012, after a recently tested rape kit turned up a hit for Ponte, according to Bristol County prosecutors.

Bristol County announced its first indictment resulting from its push to go through untested sexual assault kits in May, filing charges against Scot Trudeau in a 2010 New Bedford rape.

But the backlog of sexual assault kits in Massachusetts did not accumulate overnight. And fixing the problem has not been an overnight solution.

Rep. Natalie Higgins, D-Leominster, has been at the forefront of efforts to end the backlog in Massachusetts.

“We’re doing everything we can to help individuals involved and connected to the testing of sexual assault kits to understand the trauma, the secondary trauma a survivor goes through and that no survivor would expect that their kit wasn’t fully tested,” said Higgins, who herself is a survivor of sexual assault.

She has filed legislation related to sexual assault kits since 2017, when a law passed that allowed kits to be held without a survivor’s name attached, until the person is ready to officially file a report. As part of that legislation, Higgins said, the state lab was intended to make sure any additional backlog that existed was tested and taken care of.

Lawmakers, including Higgins, were under the impression that any backlog had been dealt with, until a report revealed an over 6,000-kit backlog held by the state lab, Higgins said.

“The idea that the small percentage of survivors who have the courage to actually file a police report with their sexual assault evidence kit was not taken seriously and just sat on a shelf, not fully tested, not fully investigated — it makes me angry,” Higgins said. “We expect that we’re going to be protected if we have that level of courage.”

That sparked new work by legislators to enact additional measures to get the kits fully tested, which has not been a clean-cut process. It involved “back-and-forth” between lawmakers and the state lab due to misunderstandings of the new laws’ intents, blamed on semantics in the legislation around the word "unsubmitted," referring to kits being held by the crime lab, according to Higgins.

“So if they were holding a kit, and they didn’t test it, they didn’t have to test it. But if a police department was holding a kit, those had to be tested,” she explained.

Under that interpretation of the legislation, around 300 kits ended up being tested, Higgins said, not the over 6,000 that were held by the state crime lab.

A Nationwide Issue

Massachusetts is not the only state that has faced a backlog of untested rape kits. It’s a pervasive issue that has impacted jurisdictions from coast to coast.

The topic has attracted attention nationwide, too. In Connecticut, funding was recently secured for timely processing of sexual assault evidence kits.

The Joyful Heart Foundation advocates for ending the backlog nationwide. It offers online resources, including a map that tracks states’ backlog counts and legislative reforms.

The organization has outlined several factors that contributed to rape kit backlogs in the U.S., including a lack of policies, which led to erratic handling of cases; biases in law enforcement; a lack of training; and the strain facing many public crime labs, caused by too little funding and too big a caseload.

Through additional efforts with the state crime laboratory, as well as local district attorneys, lawmakers were able to correct the legislation’s language to clear up any misunderstandings. The new law was passed last year, mandating that all untested kits get tested within 180 days.

Massachusetts also now mandates that newly submitted kits are turned around within 30 days — which the state said is the fastest mandated turnaround time in the entire country. The national average for turning around kits is 90 to 120 days, according to the state, and other states have been seeking guidance from Massachusetts as they work to achieve a shorter turnaround themselves.

Before recent legislative changes, the state lab needed kits to be approved for testing by prosecutors or investigators, presumably from the jurisdiction they originated in, according to the state.

The procedural change that Massachusetts lawmakers enacted expanded the number of kits that needed to be evaluated as to whether they required testing. These kits had been submitted by law enforcement, but not requested or authorized for testing. Reasons for that could have included a guilty plea by the defendant, other forensic evidence being used in the case or that testing the kit would have consumed the sample.

'Very Unseen and Very Unheard'

Imperato has worked with countless survivors during her two decades at the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center, where she is the project director of Clinical Training and Technical Assistance. In an interview, she expressed concerns about the impacts of the backlog on the survivor community.

“You have a survivor who really musters up all their courage and all their strength to then go through the evidence collection kit,” Imperato said. “And the evidence collection kit takes hours and it’s so intrusive and so violating. So, a second violation. And then to find out after all of that, the kit wasn’t processed. And I would imagine that would make survivors feel very unseen and very unheard.”

Not only that, Imperato said, the situation could even impact survivors who have not yet reported, and their decision on whether to do so.

“People are watching and they’re testing,” she said. “They’re testing the systems. They’re testing the culture to see if it’s okay for them to come forward. And, depending on people’s responses and reactions, it might not be so safe.”

Imperato noted that sexual assault is known to be an already underreported crime.

The Boston Area Rape Crisis Center tackles the issue of sexual violence — nearly a quarter of women and about 1 out of 26 men are the victims of attempted or completed rape, according to federal statistics — in a comprehensive way by offering services after someone is assaulted, as Imperato does, as well as programming delivered before assault occurs in hopes of preventing it from happening in the first place.

Casey Corcoran, senior director of Prevention, Outreach and Education for the organization, has worked with campuses and organizations all over to try and increase conversation and reduce barriers around sexual violence. Corcoran said the work doesn’t stop simply by changing laws and protocols.

“I think, for many survivors, they fear they’re not going to be believed,” Corcoran said. “And I don’t think that’s just an issue with our criminal justice system. I think that’s a larger cultural issue."

"I think it’s a very good thing that we have increased the speed that we're processing kits," he added. But I think we need to continue to push ourselves to say can we do better ... We need to constantly challenge ourselves to do more."