The ballot is deployed to replace the bullet, to decide peacefully who will lead, to resolve divisive issues and to empower individual citizens.

Whether by voice or shards of pottery in Ancient Greece, by ball, by corn and beans, lever and gear machines or touch screens, ballots were often cast in public until the United States and many other nations adopted the Australian model and allowed people to vote in private.

The ballot seals the covenant of democracy.

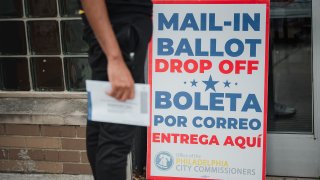

Now that civic ritual of casting a ballot has been disrupted by a pandemic and dramatically animated by social unrest. If the results of a frustrating, chaotic primary in Georgia this month is a measure, the notion of democracy itself will also be on the ballot in the November election.

Congress is now considering sending $3.6 billion to states to help facilitate safe and fair elections as part of another round of relief funds to recover from the coronavirus pandemic. The measure adds urgency to the issue of who gets to cast a ballot, and by what means, a debate that has been ongoing since the nation was founded.

One impediment to that provision: Republicans and Democrats cannot agree on a common set of facts, or even whether there should be expanded access to voting remotely in the name of public safety.

Over two centuries, access to the ballot has expanded and contracted in repetitive cycles. This latest version is largely a debate over whether to allow mail-in voting in part as a response to the coronavirus pandemic. President Donald Trump has repeatedly said — without evidence — that mail-in balloting could make the election subject to broad-based fraud.

U.S. & World

“It is under immense threat,” said Julian Zelizer, a Princeton history professor. "There is the threat, pre-pandemic, of voting restrictions that have been imposed in the states. Now there is the threat of an Election Day where people can’t vote because of fear of actual danger. Without universal mail-in voting we risk low turnout.

“The combination of the two makes this a perilous time for the basic element of our system,” he said.

A federal appeals panel recently rejected a lower court's ruling that would have allowed any Texas voter who feared contracting the coronavirus to use a mail-in ballot. That ruling will almost certainly be challenged before the full court of appeals, and the issue may well end up before the Supreme Court.

“The right to vote is a core sacred American right,” said Michael Waldman, president of the Brennan Center for Justice in New York. “But from the country’s beginning, we’ve had fierce fights over who can vote, how, and whether those votes will be counted.”

He noted that half of all states have passed new laws to make it harder to vote in the past two decades.

Despite Trump’s assertions to the contrary, in states that have relied on vote by mail, including Oregon, Washington, Arizona and Colorado, there has been no widespread fraud. Some analysts also believe that increasing mail-in voting could actually help Republicans.

“The fight over voting will be a central factor in this election," Waldman said. “It will require urgent national effort to hold an election that is safe and free.”

Elections have been held during times of war and crisis and other pandemics. "What’s new this time is that we have never had a president who tried to use that crisis to shrink the pool of who can vote,” Waldman said.

Trump has even contended that any means of increasing voting rates too much would make it far more difficult for Republicans to win, though he cited no data to support that.

Voting fraud is also as old as the country, but it is not of the kind the president describes. Like the lore of the dead voting in Chicago. Or the practice of Boss Tweed in New York who is credited with saying: “Remember the first rule of politics. The ballots don’t make the results, the counters make the results.”

Efforts to limit voting have a troubling history that has denied blacks and women the right to vote. Even with those rights, barriers like poll taxes or literacy tests were imposed to make it harder. In the Deep South, blacks were asked to name the number of jelly beans in a jar, which resulted in an almost automatic rejection by a white election official. Intimidation remains in evidence.

The last major expansion came in 1971, when the 26th Amendment was passed after a remarkably short 100 days it took to be ratified by three-quarters of the states, granting 18-year-olds the right to vote. Their supporters used the potent argument that anyone old enough to fight or die in the Vietnam War should be able to vote.

Still, even with more than two centuries of experience with elections, the fight over who gets to cast a ballot — and how — continues. And now, add a threat that quickly went from something that seemed like bad fiction to a very clear reality: the prospect of foreign interference in the U.S. election.

It is a rare confluence of profound external events colliding with questionable intentions over the most elemental aspect of the American system of self governing.

But there are hopeful signs that determined voters will not be deterred. Voters in Georgia stood in line for hours in the rain in their recent primary. Voters in Washington, D.C. also waited for hours to cast ballots in largely local races; so did voters in Wisconsin, who risked exposure to a virus to choose who should sit on the state supreme court.

“What is most distressing to me is that so many lawyers and public officials, knowing exactly what they are doing, would deliberately make it so difficult for their fellow citizens to vote,” said Walter Dellinger, a Duke University law professor and former acting U.S. solicitor general. “This is not just a difference of policy or politics. It is a shameful assault on democracy itself.”